Treebeard's Razor: The Ents Weigh in on AI Art & Writing

There is still a lot of excitement about generative AI. Clearly then, not enough cold water has been thrown on it. I am here to help.

First we need to equip ourselves with a philosophical razor, Treebeard’s Razor.

Treebeard is an Ent, a tree man character from J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Treebeard doesn’t like AI art, he thinks it’s crap.

In the following excerpt from the Lord of The Rings, Treebeard explains something about his tree people’s language, Old Entish.

“It is a lovely language, but it takes a very long time saying anything in it, because we do not say anything in it, unless it is worth taking a long time to say, and to listen to."

– Treebeard

From this I’m going to formulate Treebeard’s Razor, which you can use to trim away and discard AI art and writing. You can also use this razor to trash ghostwritten celebrity work.

Treebeard’s Razor:

If it wasn’t worth the speaker’s time to say it, it’s not worth our time to hear it, or read it, or, in the case of painting, look at it.

My formulation is much more moderate then Treebeard’s original statement (technically then I should call it the NeoTreebeardian Razor but that wouldn’t be as catchy). I’m not going to say that you have to take a long time to say something. If you can say something briefly that’s just as well.

However, what you say must at least be worth taking the time to actually say it. If a speaker is saying something of so little value that it is not worth their own time to say it, then it is not worth our time to listen to it.

“What?” you think, “Treabeard’s Razor is unnecessary because if it wasn’t worth their time to say it, and they knew that, then they simply wouldn’t have said it!” No, no, you’re wrong. Many people will attempt to occupy your time with something that wasn’t worth their time to say, and they won’t waste their own time saying it, they will only appear to say it. The saying of it they will have delegated to something else. A ghostwriter or AI.

Now, we are armed . . . with Treebeard’s Razor. Let’s start applying it. First we’ll apply it to painting. For painting we do not even need to modify Treebeard’s words into my more moderate NeoTreebeardian Razor; painting can withstand full strength Treebeardian scrutiny.

Painting is a language, a visual language. It can be a beautiful language. Like Old Entish, it takes a long time to say anything in the language of painting. It doesn’t matter if you paint fast, that’s still slow compared to how we generally communicate.

What does this tell us? It tells us that one of the statements a painter is making by choosing to communicate through Old Enti . . . I mean painting, is that the statement being made is worth taking a long time to say.

For example: look at this painting by Stanhope Forbes:

What is this artist communicating to us? Many things, but not least of these is that the artist has told us that commoners, out and about on a shiny beach during a gray day, doing their ordinary fish market tasks, are so important, such worthy subject matter for study and contemplation, that it is worth his time, attention, and hard won skill, to carefully portray them as he has done in this great work. The observation, time, and energy the artist dedicated to this portrayal is a major statement in itself.

Now let’s look at another painting:

Maynard Dixon isn’t merely stating that the desert landscape is worthy of dedicating years of his life to studying, feeling, learning from, and sharing what he has found with his audience (us) – he has proven that he believes this, for he did indeed spend years of his life doing just that.

Is it worth our time to contemplate and be transported by paintings? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. Depends on the painting, BUT, odds are good that the answer is in fact yes. Why? Because the artist doesn’t merely profess that the painting is worth looking at, the artist had to put their time, and if they used high end materials, a chunk of their money, where their mouth is. So we very nearly have proof that the artist is in earnest. They really did think their statement was worth taking a long time to say.

The Ents would approve.

Yes, I know, lots of celebrated artists this past century or so have been deluded and their judgment can’t be trusted on much of anything. But, for those whose judgment is at least halfway decent (this is an important caveat), the painting is strong evidence that they thought the statement worth taking a long time to say – and while this does not guarantee that it is worth your while to look at it, it does increase the odds that it is.

Now let’s take Treebeard’s Razor (just the more moderate NeoTreebeardian formulation) and apply it to AI art. Is it worth our while to look at AI art? In general, no.

If it’s not worth the artist’s time to say it it’s not worth our time to look at it.

The great innovation of AI art is that it allows you to make visual statements that aren’t worth taking much of anytime to say.

“Want to say something, but don’t think it’s important enough to bother investing your own time, thought, and energy into saying it? Boy have we got the answer for you!” - AI art.

This same principle applies to AI writing too.

The purpose of writing isn’t content generation, it’s communication. Ideally you put your work in front of people because you had something worth telling them. Content generation for the sake of content generation is an act of vandalism that pollutes the information commons with garbage that people have to wade past, making it more difficult for them to get to meaningful writing (or imagery).

Imagine someone creating a machine that can churn out semi plausible sounding gibberish and using it to fill books with plagiarism and derivative hackwork, and then putting nice sounding titles on them and stuffing a library with them. Patrons would then have to sort through all the junk to get to the original works, thereby making the library less useful. That’s the equivalent of having AI generate content and then diluting the original work on the internet with the AI derivatives.

For someone to put a platter full of AI content in front of us for our consumption is an insult to the audience. Let me give you an example of why with a little story:

Mr. Busy Calls his Mother

Mr. Busy’s mother was surprised to receive a phone call from her only child on Christmas. He never called, he was too busy. She used to invite him to drop by for coffee or lunch to catch up but he was always too busy. They met maybe once a year despite living in the same city.

She was pleased that he had made time for her at least on Christmas. She answered the phone and they talked for, to her surprise, 20 whole minutes. The next month he called again; at first she was worried that maybe an emergency had happened.

“Ha ha, no no, I’m fine mom, I just wanted to check in, see how things are going and chat a little.”

Later that year at the family reunion Mr. Busy’s mom asked him about the sky diving trip. Mr. Busy looked perplexed.

“Sky diving trip?”

“Yes, you said that you were going to go sky diving when we last talked, remember.”

“Oh, no, that must have just been an AI hallucination.”

Now it was Mr. Busy’s mom who looked perplexed.

“AI hallucination? What are you talking about?”

“Ah, well you see, I felt bad about never making any time for you mom; I’m just too busy you know, but thanks to technology I can call you every month despite my busy schedule. The program is called KSAI or Keepintouch Solutions AI.

It uses information from all my previous phone calls, conference calls, and social media to recreate my voice, and converse with you like it was me. Don’t tell her, but I have it call Samantha and Johnny (Mr. Busy’s wife, and son) when I’m away on business trips too, it saves me a lot of time. Of course they’re probably using Keepintouch to answer my calls too; in which case it would just be AI talking to AI, ha ha, imagine that! I’ve even been using it for courtesy calling my less important clients, makes them feel like they’re important.”

“Oh, now mom! Don’t act all hurt and offended like that. You said you were delighted to hear from me more often. Don’t let the knowledge that it’s AI ruin it for you, it’s still based on me.”

— The End.

I think that gets the point across well enough at just how offensive it is to pretend to say something to someone by delegating the task to a machine. This demonstrates that you in fact had nothing to say, and value their time so little that you occupied their time by pretending to talk to them anyway.

This deep insult to the audience is much older then AI. Politicians and celebrities have long expressed unadulterated disdain for their audience by doing something like this by using ghostwriters.

For example, Kristi Noem (Current Secretary of Homeland security and former South Dakota governor), received blow back from her now notorious story about shooting her puppy or something, in her book No Going Back. But far more interesting is that the book also included an anecdote of Kristi Noem’s meeting with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un – a meeting that never happened. The controversy then revolved around whether or not Kristi had told her ghostwriter and publisher to include this story or if it was an innocent mistake with the ghostwriter and publisher having taken liberties.

That there could even be any question as to whether or not this was written without Kristi Noem’s knowledge of it, reveals just how uninvolved Kristi Noem was with the writing of her book; not only did she not write her book, she might not have even read it.

The biggest scandal of Kristi Noem’s book No Going Back isn’t the puppy (rest in peace) or the potentially blatant lying, the deeper scandal is how little she values other people’s time, and that she polluted bookstore shelves with garbage. I’ve never read her book and never will, because I already know that it is not worth anyone’s time to read it. She didn’t have anything to say. Or at the very least, whatever she may have had to say was so unimportant that it wasn’t worth her own time to say it.

Had she had anything worth her time to say she would have said it and would then have had no need for a ghostwriter. (I sort of want to like Noem for having not gone crazy on Covid-1984 like the other governors, but I’ve chosen to use her as an example anyway, and denounce her crime of polluting the information commons because I don’t feel like finding another example from another politician or celebrity).

So AI is in some ways the poor man’s ghostwriter (or ghostpainter, or ghostphotographer). Now rich and poor alike can pollute the information commons with visual and verbal statements of so little value that they’re not worth the author taking their own time to say them.

This is the pointlessness of generative AI: Do you have something to say?

Yes – Then say it.

No – Then don’t occupy people’s time and or visual space (in the case of AI art) by pretending to say something.

“But if you can say something faster and more efficiently why not?”

Why not indeed. Look at this vivacious work by Fragonard painted in 1761 (sorry about the “fish eye” camera lens distortion; the colors and resolution on this image were better than others available online).

On the back of this painting was an old note stating painted in one hour’s time. Whether that boast is true or not Fragonard was fast, and the painting is great, but Fragonard still said it. This visual statement, is Fragonard’s statement. It was worth his time (one hour), and his intense focus (necessary to pull this off), to make this visual statement.

If Fragonard had been alive today, and had saved himself the trouble on this painting by entering a prompt into AI along the line of “Painting of young man in colorful clothing,” then Fragonard would have saved himself an hour and some energy. He also wouldn’t have said anything at all; he would have merely prompted a machine to churn out some visual content.

Entering a prompt into an AI program to generate visual content is no more painting then hiring a ghostwriter is writing. We come back to the same pointlessness of generative AI. If you have something to say, and it’s worth your time to say it, then just say it, you don’t need AI or a ghostwriter. If you have nothing to say, or it’s not worth your time to say it, you still don’t need AI or a ghostwriter, because it simply doesn’t need to be said at all then.

A Couple Possible Objections that I’m Going to Preemptively Address and Dismiss

1st Objection: Not everyone can paint, AI lets everyone paint, it democratizes painting.

No it doesn’t, it’s not letting anyone paint, because the user isn’t painting at all, and no, the image prompt doesn’t count as painting either or anything like it. Here is why:

First, look at this painting:

Why did the artist go through all that trouble of actually painting the image? Wouldn’t it have been easier to make a simple written statement like: “ woman kneeling at a grave with an umbrella, hills and building in the background, green grass and some wildflowers in the foreground”? There, see, that required next to no time for me to write that, yet it must have taken Nono weeks or more to paint that painting. So why did he go through all that trouble?

Because the artist is trying to do something that cannot be achieved with a simple written statement. Whatever the artist is exploring/channeling/expressing requires going beyond a simple written statement or else the artist would have saved himself the trouble and given us a simple written statement instead of a painting.

But what do you put into an AI image generator? A simple written statement like the one I just provided. So everything beyond the written statement isn’t you speaking, it’s the image generator filling in based on its programing. That’s what I mean when I say that you aren’t saying anything at all with AI art. Your part is the written prompt; everything beyond the written prompt for the image generator doesn’t have to do with you. But everything beyond the written prompt is everything that matters, because painting is getting at things that you can’t get at with a simple written statement: otherwise no one would bother painting to begin with, but would instead just make simple written statements.

2nd Objection: “But many people do use AI art, especially for illustration work – article and editorial illustrations, children’s books, and so forth, so clearly it must be serving some value or else so many people wouldn’t be availing themselves of what it offers.”

Yes, clearly it is performing a function, but what is that function? I’m going to argue that that function isn’t primarily to make imagery, but to get (access) imagery. AI art programs serve as a stand in for a sophisticated search engine, access to most the world’s images, and a magical copyright begone wand.

If the same money put into AI art programs had been put into scraping all the images off the web, but instead of using them as the basis of AI art using them as a free to everyone image library searchable with an extremely responsive search engine, then I bet that this would be even more useful for most purposes (especially article images and illustrations) than AI. Most of the time when someone uses an AI image there’s a very good chance that there is an original painting or photograph out there that would have been even better for their purpose, but they either couldn’t find it (save by finding it as a derivative in the form of AI art) or they could find it but couldn’t use it because of copyright, watermarks, or too low of resolution.

So a massive repository of images, a very responsive search engine, and a magical copyright begone wand are all real functions of AI art programs, but none of those actually have to do with creating artwork; they all have to do with archiving, retrieving, and removing copyright.

Let me show you a hypothetical: suppose I wrote a space science fiction book, decided I wanted a nice dramatic cover for it, and so I wrote a prompt into an AI image generator. All I say is in the style of John Harris, that’s it: I literally wrote that right now and got this:

Okay, well, clearly the image generator has in it’s data base the works of the English artist John Harris, known especially for his science fiction covers, because I didn’t say space based. The image generator mostly kicked out space-ish sci-fi though, so they must have his works tagged along those lines. Some users are probably getting derivatives of John Harris without even realizing it when they put in space related prompts, not to mention many other artists whose works are being copied with enough machine alteration that we’ll never learn whose art we’re actually looking at (in derivative form).

But I didn’t need that derivative image above; nobody needs it; it added nothing to the world, there already existed something much better:

The AI prompted derivative is nowhere near on par with the original John Harris painting (above) that it appears to be somewhat based on, and the same could be said for all manner of AI art - on the rare occasions when you can figure out what the source material is for the AI, the source material is almost always better. But, in my hypothetical situation the AI is serving a purpose . . . as a copyright begone wand. The original John Harris above is copyrighted, whereas the AI derivative would be unlikely to face a copyright challenge.

Provenance

Messages generally do not exist in a vacuum. Who said it, when they said it, where they said it, and how they said it, are all aspects that can contribute to, and alter the meaning of the message. AI black boxes that do not allow us to see what the imagery is based on strip away all this information. Multiple layers of meaning are removed. AI images are atomized images. In contrast paintings are enmeshed within the webs of human societies, individual lives, and specific times and places.

Let’s look at some examples:

The Raft of the Medusa (above) was controversial, because it is a dramatic, vast painting (16 by 23 feet), of proportions and seriousness usually reserved at the time (1819) for high, noble, biblical, mythological, and historical depictions. But what this painting depicts is in fact scandalous. A sensational shipwreck with the captain’s competence called into question, that led to the death of most the crew, with survivors resorting to cannibalism.

Was it worth this artist putting an immense amount of time, energy, research, and expense, into creating a monument to that tragic and sordid event? An open question. I like the painting, though personally I’m with the critics from two centuries ago on this one — I don’t think the subject justifies the monumental proportions and effort.

No AI art will ever lead to such a scandal and such a debate because there is no threshold at which something becomes worthy of being painted with AI.

Late 19th century paintings celebrating ordinary people, farmers, fishermen, children, and peasants, have sometimes been derided as “sentimental” by ivory towered - art world - air headed - smooth brained - know nothings. On the contrary, there is nothing wrong with sentiment, and these late 19th century paintings are remarkable. These paintings represent artists dedicating the same time and skill that used to be reserved primarily for paintings of kings and queens and high subjects - to painting peasants. So I think you can see some very positive social significance to that.

AI art does not have such social significance. The medium cannot convey a comparable message of loving time, care, skill, and attention dedicated to the subject.

Even when it comes to weirdness AI art can’t match the weirdness of real art. Anyone can get a weird image by prompting AI, and what of it? That’s just goofing off. In contrast it takes a real weirdo to dedicate hard won talent and and skill to envisioning and summoning into this world a weird vision to be shared with the audience. For example: knowing how serious and dedicated Cormon had to be to plan out and see through to completion his epic painting Cain is part of what makes it so delightfully deranged.

Direct Experience

Every artist’s work will be partly derivative, based on influence and inspiration from other artists who provide the foundation that they’re building on. But their work will also involve their own observations of the world. Real life and the real world are breezes that continually freshen up and ground the artist’s work. For example, we can feel Maynard Dixon’s own experience of moonlit nights informing his painting Roadside.

But of course AI is never going to draw upon its own experience of a moonlit night. Rather than combining inspiration from other artists with its own experience, AI is entirely derivative.

In Summary

Mediums are there to convey messages. Nobody needs content for the sake of content. There exists already a vast quantity of written and visual material. The principal issue isn’t a shortage of content; the issue is quality content getting swamped by junk content. The main contribution of generative AI has been, and most likely will continue to be, making the problem worse, by increasing the quantity of junk derivative work that we have to wade through to get to high quality original information and imagery.

Ah, the wonders of big tech - right when the internet was already drowning in garbage from clickbait and hackwork they came along and provided us with a state of the art junk generator like no one had ever seen before.

Speakers (as in communicators) who have something of value to share with us will share it by saying it themselves through writing, painting, speaking, photography or some other medium of communication. If someone delegates the task to generative AI, that is a sure sign that they either had nothing to say, or that what they did have to say wasn’t worth taking their own time to say, and consequently isn’t worth our time to listen to or look at.

P. S. If you are a writer/content creator, you are more than welcome to use images of my paintings off my website as illustrations for your own blog posts, and videos as needed. I only have some 50 or a 100 images up online, but still, every bit helps to reduce the use of generative AI. Should you take me up on this, please just credit the image source with my name and a hyperlink to my website page where you found the image.

Conciliatory Note:

In this essay I have shown no mercy in my trashing of AI art, and I should have kept it that way because that was fun. But unfortunately I struggled with my inner angel (damn him). He got the better of me, marched me back to the keyboard, sat me down, seized the controls to my arms and hands, and forced me to write this conciliatory note (that’s the real danger of letting my essays sit for so long before publishing as I generally do; it gives that nasty little goody two shoes too many openings to slip words in edgewise).

So here’s the thing - many independent writers, podcasters, and documentary makers, whose work is of a high quality, and clearly a labor of love, do use AI for much of their imagery. I would not want to demoralize, or denigrate these hardworking communicators, and to be fair (and it looks like I’m going to be fair now, I guess . . . because of my whiny, killjoy, oversensitive, conscience that keeps intruding on my writing) they have a legitimate (?! . . . Well, how about at least understandable) reason for their use of AI.

Namely, they are usually verbal communicators, who use written and spoken words to convey their message, not visual artists. They are under no obligation to provide any imagery at all to accompany and enhance their verbal message, meaning that even when they use AI for their imagery, that represents them going above and beyond and putting in more work, not less, into the crafting and delivery of their message. They are creating multimedia productions and delegating to AI the visual imagery part at which they are not themselves specialists.

So maybe I should appreciate their effort rather than harshly condemning them? Well I do in fact appreciate their efforts, and I enjoy many indie media productions, but appreciating their use of AI art? That’s a bridge too far, but I’ll compromise; I’ll hold off on the condemnation . . . or, well . . . I won’t heap it on so thick. They don’t have my blessing for their use of AI art, but they do have my understanding.

I understand that they are still playing an active role in their use of AI through selective editorial decisions and using the imagery to set the tone and visual ambiance. For the same level of effort they may be getting more exciting, personalized, and appropriate imagery than what they would get by hunting through free stock photography and clip art which look like they might be getting sloppified by a flood of AI junk anyway.

As I mentioned earlier in this essay AI has had so much money and effort poured into it that in many ways it is a huge image library (maybe the biggest ever) with more images, and a more responsive search engine than other image repositories. And of course the copyright begone magic of AI art let’s you draw upon even bodies of modern sci-fi and fantasy art (in derivative, degraded form) that would otherwise be protected by copyright.

So there, see, I am understanding, merciful, and magnanimous. Can my inner angel please let me go now and end this commie struggle session? Good, thank you. So all that being said, I encourage content creators to think about the imagery they use not just as a decoration, or ambience setting; instead think about doing this:

When you can, use your illustration needs to draw attention to original works. The images free of copyright concerns are usually going to be older works of art and photographs. Where applicable use them instead of AI. Credit the image source and drop a few details in (name of the artist, year of the work). I don’t think that I am alone as a reader in being more impressed by an article illustration where the author or editor used an old artwork instead of AI - because suddenly it’s not just a decoration on the article - it’s a curated selection, it’s a historical connection, and it’s a step in re-popularizing painting.

Again, AI art is atomized and disconnected - paintings, on the other hand, are enmeshed within human society and history. We have lost much of the connection with the bodies of visual work from the past. That’s not AI’s fault. Painting was cast down from its prominent position that it held in the late 19th century, not by any new technology, but by the hostile takeover of the artworld by anti-art Emperor’s Taylors (after their success making him his new clothes they set about popularizing the Emperor’s New Art) who alienated the public from painting.

The public, from all walks of life used to crowd into the salons every year to see the works of their nation’s visual artists. The hostile takeover of the art world by the Emperor’s Taylors drove out the good art, and elevated Emperor’s New Clothes style art (blank canvases, upturned urinals, sharks in formaldehyde, Campbells soup cans, etc.) and through this they alienated the public from painting.

Good art never stopped being produced, it just lost most of its official, and institutional patronage. A contemporary artist like John Harris, for example, (who we looked at earlier) found patronage for his work through science fiction book covers. In two books published on John Harris’s work (Beyond the Horizon, and Into the Blue) the introductions mention that John Harris drew inspiration from the Romantic art movement of the 19th century, and the Orientalists, so we can see that a modern science fiction artist is connected to the historic flow and web of visual art movement stretching back centuries.

Let’s pause a moment to appreciate Meckel’s painting above. The original is over six feet across the long side, so of course we’re not going to get the full impact from a picture of the painting, but we can still get a lot. The composition is strong, and stands out clearly even at a thumbnail scale (so it would grab your attention from across the room when seen in person). There’s plenty of breathing room, it’s bright and airy. Yet, when we inspect the details (which Meckel wisely concentrated/grouped so that they contribute to, rather than ruin the composition) we find ourselves enjoying an almost Where’s Waldo? type of fun.

The woman in the lower left of the composition smoking a cigarette is smiling at something funny or mischievous said by someone with their back to us. The rocks behind her are lit from beneath with warm light bouncing off the sand back into the shadows. The man to her left, the most prominent figure in the piece, looks like he has stopped in to chat while about on other business. Deeper into the painting we find women washing clothes, and goats and donkeys on the bank. A brilliant extravaganza.

Continuing with the contemporary artists connection to the past: the artist Steve Henderson (my dad) has an almost encyclopedic knowledge of artists and art movements, stretching from renaissance Italy and 19th century Russia into early 20th century American illustrators. So he is deeply informed by and connected to the historical flow of visual communication.

(In the Witching Hour above, I like it that, despite the title, there are actually no overt symbols of magic; all the magic needed in this case, is in the gathering dusk, the dark trees, and the shimmering water surrounding the woman’s central figure.)

The flow of realist imagery, in for example, oil painting, runs unbroken from headwaters in the late middle ages right down to the present day - for some. But for much of the public the connection is broken.

That’s where writers can elevate their article illustrations beyond mere decorations. Each illustration, if you can find a suitable pre-existing image, is an opportunity to re-familiarize and reconnect the audience with the flow of visual communication - a place where you can use those visuals to highlight great original creative works rather than merely generating more machine made derivatives.

For old artworks, no problem, if they’re old enough to be in the public domain, high resolution images through Wikimedia commons, auction houses, and museums, are getting easier and easier to come by. Late 19th century works tend to be especially accessible to, and easily appreciated by, a modern audience.

For contemporary artists - well, it’s up to us, the copyright holders, to give permission to indie media creators to use our art as illustration in their blog posts and videos. And I would encourage contemporary artists to consider doing that, because the AI programs have probably already scraped your images off the web and are using them to make derivative artwork; wouldn’t you rather that your original creative work go out instead of anonymous derivatives of it? And that way you at least get credit for your work.

Closing Thoughts

I really am going to end this essay before wandering off on another tangent, so don’t worry, any paragraph now I’ll end this essay. But first, a couple last thoughts:

Encouraging Snobbery

The public tends to hate AI art. They’ve become art snobs. That’s wonderful, and I hope that my essay here will serve to embolden the AI art haters. While not all uses of AI art are damnable offenses (maybe just purgatory), any attempt, though, to place machine made derivative art images alongside natural intelligence, man made art, is a crude insult to human agency and organic sources of inspiration.

Expecting the audience to take machine made derivative art seriously is unreasonable and the audience is right to be offended by this.

I encourage people not to let fears of hypocrisy get in the way of practicing snobbery towards AI art:

Let’s say that someone sees an image and they love it. But then they find out it’s AI. Now they want to withdraw their approval, and instead actively dislike the image, but they think that might be hypocritical of them. That now they are somehow bound to continue liking the image. But no, they are under no such constraints.

It is always acceptable to change your mind based on new information. It is perfectly legitimate to begin disliking an image that you initially liked after you find out it’s AI.

Remember, communication doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Who said it, how they said it, and so forth, are factors that can change the meaning of a statement, such as a painting. As you find out more about an artistic statement, it is natural, and right, and healthy, that your opinion of the work evolves and changes.

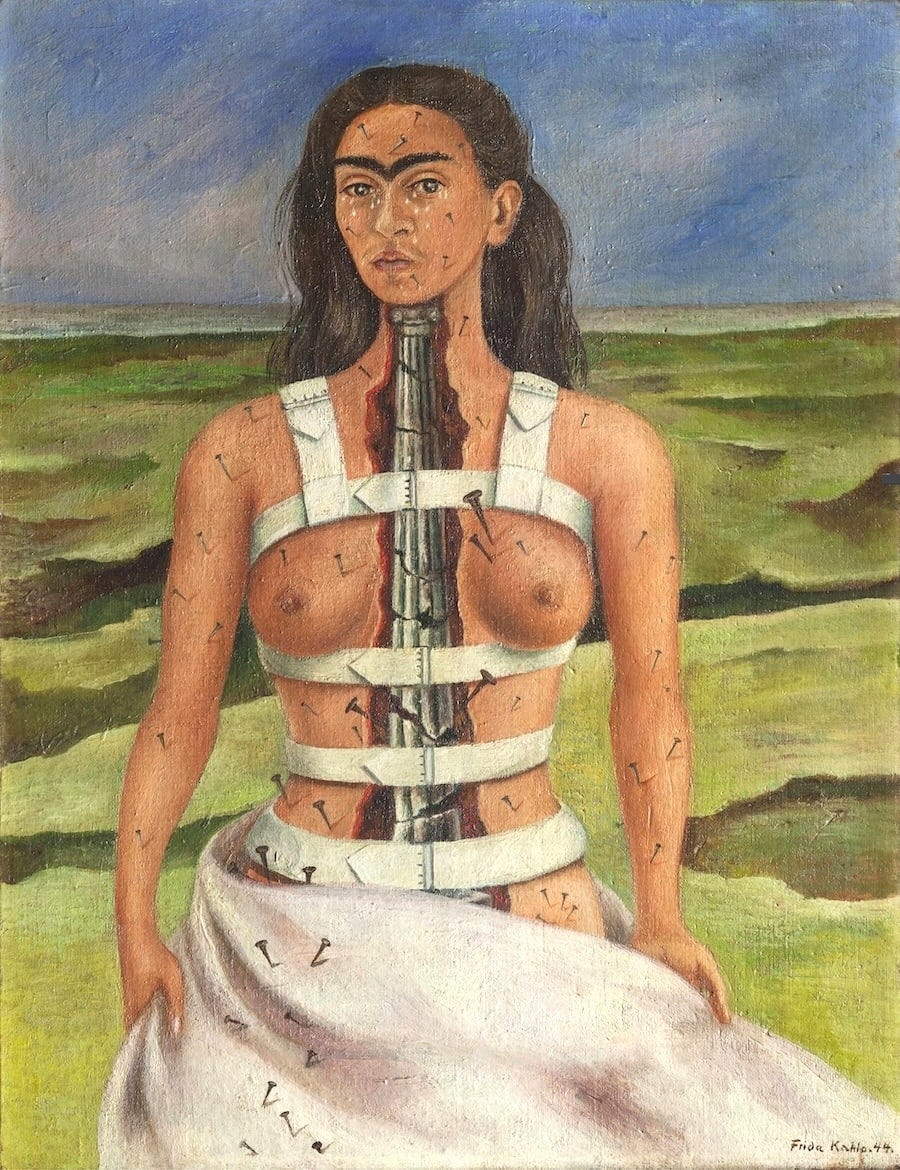

For example: I initially disliked Frida Kahlo’s work - wasn’t my cup of tea, but as I found out more about the pain and struggle Kahlo endured and used her canvases to express, my opinion changed, now I can appreciate her work to some degree.

A terrible bus accident with a trolley impaled Kahlo’s pelvis with a handrail, broke her spine in multiple locations, crushed her foot, and a long list of other injuries left Kahlo with recurrent pain and illness from that point on. The Broken Column is an example of her working through her pain on canvas:

As another example of someone reasonably changing their view of an artwork based on new (to them) information, let’s look at Fragonard’s The Swing.

My sister used to love this painting . . . till she found out that the man in the bushes is looking up the skirt of his mistress, while her husband in the shadows propels her on the swing. Then she wasn’t so enthused about this painting anymore. That’s a reasonable reassessment. The painting at first seems sweet and enchanting but upon closer inspection is sullied by the questionable subject it portrays. It seems to me to represent upper class moral rot, but celebrates and trivializes it rather than criticizes it.

The first artist approached with the commission, Gabriel François Doyen, is said to have refused the commission, and it would have been to Fragonard’s credit if he too had turned it down.

As a final example of why it is appropriate to dislike something you initially liked, upon finding out more about it, such as that it is AI, there is of course the story I provided earlier in this essay Mr. Busy Calls his Mother, where Mr. Busy’s mother went from being happy about her son touching base by phone, to being offended when she gained new information about the phone call - that it was AI. And I think we would all see her change of mind in the hypothetical story to be justified.

Honest to Goodness, Final Paragraph(s), For Real This Time

By this point it’s probably started to dawn on you that this essay doesn’t have much to do with Treebeard. You may be wondering how much it really even has to do with AI art. That only 1 image in this essay, out of 22 images, is AI art is perhaps a little suspicious.

Well, AI art provided a good foil for discussing real paintings. If you weren’t enthusiastic about paintings before, I hope that some of my enthusiasm has rubbed off on you. If your snobbery towards AI had begun to waver I trust my arguments will have renewed your aversion to it. And finally (really), if the pretentious word salads of the art establishment had alienated you from paintings I hope that my plainspoken essay will have brought you back.

This essay was first published on Winter Oak, and Off-Guardian.

Jordan Henderson is an artist from the Northwest of the United States. His original paintings can be Viewed Here, Art Prints Here, and Essays Here.

Good stuff!

AI is the ultimate visual-art/image pollution tool … or as you say “...content for the sake of content” resulting in “...quality content getting swamped by junk content.”

“...AI art is atomized and disconnected” — Which is the point perhaps, as decontextualization leads to meaninglessization, which in turn, leads to demoralization ... which would appear to be the ultimate goal, since demoralization is fundamental to facilitating enslavement.

PS: love the third Ent face and the hands-on-hips squirrel.

Wonderful! In one sense it’s coals to Newcastle for me. I have detested AI as garbage and deceit and theft, but your thoroughgoing and delightful essay strengthens and undergirds my detest. 🙏 many thanks. And thanks for so many powerful images.